I remember, vividly, my first encounter with the mob. Afterwards I was an angry, upset and, most of all, confused (novice) improviser. Licking my wounds, I was attempting to piece together what exactly happened; trying to figure out exactly why I was angry.

…People who use anarchy of collective improvisation will interpret that [‘freedom’] to mean ‘Now I can kill you’…. …Any transformational understanding of so-called freedom would imply that you would be free to find those disciplines that suit you, free to understand your own value systems; but not that you would just freak out because ‘the teacher’s not there’.

Anthony Braxton quoted in Lock (1988), p. 240.

Let’s get a few things out of the way. By the mob, I don’t mean noise.

Noise is that super-saturated, information rich, contradictory musical experience—really, I can’t get enough of it. Nor do I necessarily mean ‘playing as fast as you can, as loud as you can’—another standard complaint against improvised musics. Velocity and power are things that… well, that’s a story for another time.

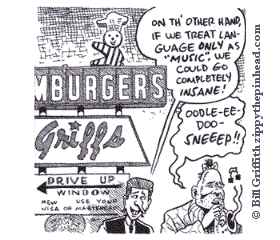

No, what I mean by the mob is, to put it ineloquently, the

moosh. You want the evil mirror image of

contrasts and juxtapositions? Well, there it is: We are all the same, we are marching lock-step, we never ask why, and if someone does, we won’t hear them and we’ll make sure that they can’t be heard.

Mob behavior, in improvised contexts, is a strange thing. Sometimes I think that it shouldn’t exist at all, other times I’m surprised that it appears so infrequently. It’s as if the twin, seemingly incompatible, rhetorical ideals of improvisation (at least among many ‘part-time’ improvisers)—of individualism and collectivism—collude together to construct the mob.

So, do we want to be

leaders, or do we want to be sheep? Maybe these are not as distinct as may appear. Maybe to be seduced by the notion of leadership is to become unquestioning followers.

You’re either with us, or against us….

George W. Bush, November 6th 2001.

What happened that evening of my first encounter with the mob? Those that could blast out, did; those that could not, had their voices taken away.

So I’m watching, for example, a couple of brass players who were, by day, straight laced orchestral types, now ‘free’ from the discipline of the idiom (score?), ‘free’ from the command of the ‘teacher’ (conductor?), were doing their best to drown out others whose instruments were not as capable of such volume. The irony being that I couldn’t make out what they were playing either.

After that bruising and disorientating experience had finished, an excited percussionist came up to the instigator of the event. Many mutual congratulations were exchanged. The percussionist talked about the symbolism of the group playing with one voice, and drowning out—indicating my little amp—the symbol of power. (I was too angry to say this at the time, but, oh, man, you couldn’t hear me ’cause I wasn’t playing. And anyway, you know I had the volume of my amp at the one quarter mark—I could have drowned out every single one of you

easily: as easy as turning a dial, as easy as pushing a button—

boom.)

All this was for a ‘consciousness raising event’ to stand against, I kid you not, the mob in Bosnia. How’s that for irony?

How many sins have been committed in the name of political purity?

…How often have we heard that Communism, or Socialism, or free-market economics, or cost-benefit analysis, or monetarism, would bring the good life (for those who remained) if only they were systematically imposed and all the deviant elements were rooted out?

Law (1994), p. 6.

We’ve been trained not to like difference or contradictions, or at best to keep it safely bound and fenced off. We may desire to be the same (we want

coherence). We may desire societies composed of the like, rather than the different, because we believe that a heterogeneous society is no society at all. If we start believing that, we might just start to act like the mob. We’ll become sheep or (

mythical) lemmings because we cannot, or will not, take responsibility for our actions. But that’s a subject for another time….

some (unanswered) questions:

How does Taylor do it?Is it just me, or does Cecil Taylor’s larger scale performances fly close to mob behavior? How does he manage to navigate clear of it? Or does he? Is it that there is such a charismatic figure in the middle of it that prevents it swinging out into that

moosh?

What can you do in the middle of that mob?In subsequent encounters with the mob, my solution was to walk off stage. That never seemed to me to be an entirely satisfactory solution. It always felt dishonorable….

Does the lack of an explicit idiom act as a catalyst towards mob behavior?Just informally, I’ve encountered this mob in the form of orchestral players and/or neo-boppers (exceptions in both cases of course) more often than others. Is it that they, more than others, feel that, when the safety-net of the score or idiom is taken away, the ‘teacher’ is out? Alternatively, does this become a collective therapy session to let loose and (primally) scream? Is it then unfair of me to say that this becomes ‘freedom’ for people who take freedom for granted?

references:

Law, John (1994), Organizing Modernity (Oxford: Blackwell).

Lock, Graham (1988), Forces In Motion: Anthony Braxton and the Meta-reality of Creative Music (London: Quartet).